Triplets

Hello reader! If you’re not a fan of reading about programming puzzles then feel free to skip ahead.

I have spent a fair bit of my recent free time solving coding puzzles for fun. The reason for solving these puzzles is to stay sharp on algorithms, data structures and language syntax (C++ for now) as my upcoming school semester is going to be computer science course free. I also can’t forget to mention the main reason: to experience the sweet sweet feeling of ecstasy when you solve a puzzle after a few hours of thinking, coding and debugging.

I have started with hackerrank as it has a vast collection of puzzles you can solve and keep track of your progress with respect to other users on the website. The puzzles are organized by the domain of expertise required to solve them with varying levels of difficulty - from very basic to insane. Hackerrank provides the user with the ability to code up their solution (usually in the language of their choice) to the puzzle and submit it for testing to get immediate feedback. If the user’s solution passes all the provided test cases then the user is considered to have solved the problem and gets points for it (let us take the time to remember that passing all the test cases does not mean that the solution is necessarily correct {you could have always missed an edge test case} ~ you need a formal mathematical proof for that).

Oftentimes the problems have a very basic brute force solution that are very slow computation wise. However, hackerrank prevents you from submitting these types of solutions as their servers have tight time limits and large inputs for your solutions and thus they push you to do some extra thinking in order to avoid the brute approach.

I thought for this blog post I would present my solution to the triplets puzzle from hackerrank in order to share my solution, practice explaining my train of thought in written form and maybe infect the user with a desire of solving puzzles.

I will do my best to assume minimal experience with computer science related knowledge. This will probably add even more confusion for which I apologize in advance.

Puzzle description

The puzzle description is very short and I will just paste it from the website:

There is an integer array which does not contain more than two elements of the same value. How many distinct ascending triples (d[i] < d[j] < d[k], i < j < k) are present?

The puzzle description may be short but it tells us a lot of information. Let’s start with an example array d :

d = [1 1 2 2 3 4]

The distinct ascending triples for d are:

(1,2,3)

(1,2,4)

(1,3,4)

(2,3,4)

so therefore there are 4 triples present.

In our example the first triple (1,2,3) = (d[0 or 1],d[2 or 3], d[4]), 0 or 1 < 2 or 3 < 4 assuming we start indexing d at 0. The or in the indexing choice tells us that there are technically more than one triple of ascending triples with different indexing that work up to being (1,2,3), but we are only looking for distinct triples.

Reaching the solution

Attempt 1

For the test case discussed above one may notice that the array is already in ascending order. In fact if we knew that they array would always be in ascending order then all we would have to do is let n = # of unique numbers in d and output n choose 3 (all possible combinations of choosing 3 random numbers from n numbers ~ order of selection not mattering).

However, the array being ordered is not guaranteed and even with the same numbers in an array but different order we can get different results. Consider the numbers:

1 2 3

If d = [ 2 3 1 ] we get 0 distinct triples whereas if d = [ 1 2 3 ] we get 1 triple.

Attempt 2

Since order matters we can get a sense that the solution as it is parsing the array number by number sequentially needs to keep track of the past data. One thing it can keep track of is the numbers that are to the left of it and smaller. Since we are processing the numbers sequentially and looking at the past then the current number being processed must be treated as a potential candidate for the third position in a triple as we have no way of looking forward.

However, if we think carefully then we can come up with a set of test cases that would stump our current approach. Let us say that the array d = [ x y 3 ] where we are currently processing d[2] = 3 element. We are now looking at the number of elements d[i], i < 2 where d[i] < d[2] (looking at all the numbers that come before 3 such that they are smaller than itself).

If at least one of x and y is bigger than 3 then our approach tells us that there are not enough numbers before 3 to form a triple with 3 as the last element. This is the correct answer.

Now if both x and y are smaller than 3 then we are in trouble. There are two possibilities: x < y or x >= y, but there is currently no way for 3 to tell which one is true. The former should give one triple and the latter should give 0. Our current approach is left up to guessing the answer. This definitely would not scale well. It turns out we still are not handling the concern of order.

Attempt 3

To get over our previous stump we either have to be able back track in the array (which sounds like too much work) or we can process the data differently.

One way of going through the list differently is to treat the current number being processed as the middle candidate for a triple. This will allow us to avoid the problem of figuring out the ordering of the first two numbers. We now will only care about which numbers are smaller and to the left of current number and the numbers which are to the right and bigger of the current number. The trade off here is that we will have to now be able to look ahead in the list in addition to looking back. This implies that the array will have to be processed at least once in advance for us to have this ability.

If the current number x has a total a numbers before that are smaller than it and b numbers after x that are bigger than it then we can figure out the total count of triples with x as the middle number. This number must be a * b. For example: d = [ 3 2 4 8 7 ] and x = 4 then a = 2 and b = 2 meaning that we get a * b = 4: {(3,4,8),(3,4,7),(2,4,8),(2,4,7)}.

If we iterate through all the numbers in the list and sum up all of the a * b products then we should get the total number of distinct triples … well almost. One thing we have not considered at all so far is the “does not contain more than two elements of the same value” phrase from the initial problem statement. The case d = [ 1 1 2 4 ] would not work well for our current approach (since for x = 2 there are two numbers smaller than it and to the left, but they are the same number ~ something our algorithm cannot currently distinguish).

Attempt 4

The two element issue we will discuss a little bit later. For now let us consider the specifics of “keeping track” of past data. We have mentioned it a number of times but we never discussed the details. How do we keep track of the numbers that are smaller and to the left of a number in an array?

One way is to go and parse all the numbers to the left one by one and count that numbers that match our description ( a little too slow).

A better method is to construct a modified binary search tree. If you don’t know what a binary search tree is then please read more about it. I apologize for this extra reading, but it saves me from typing up a LOT of stuff.

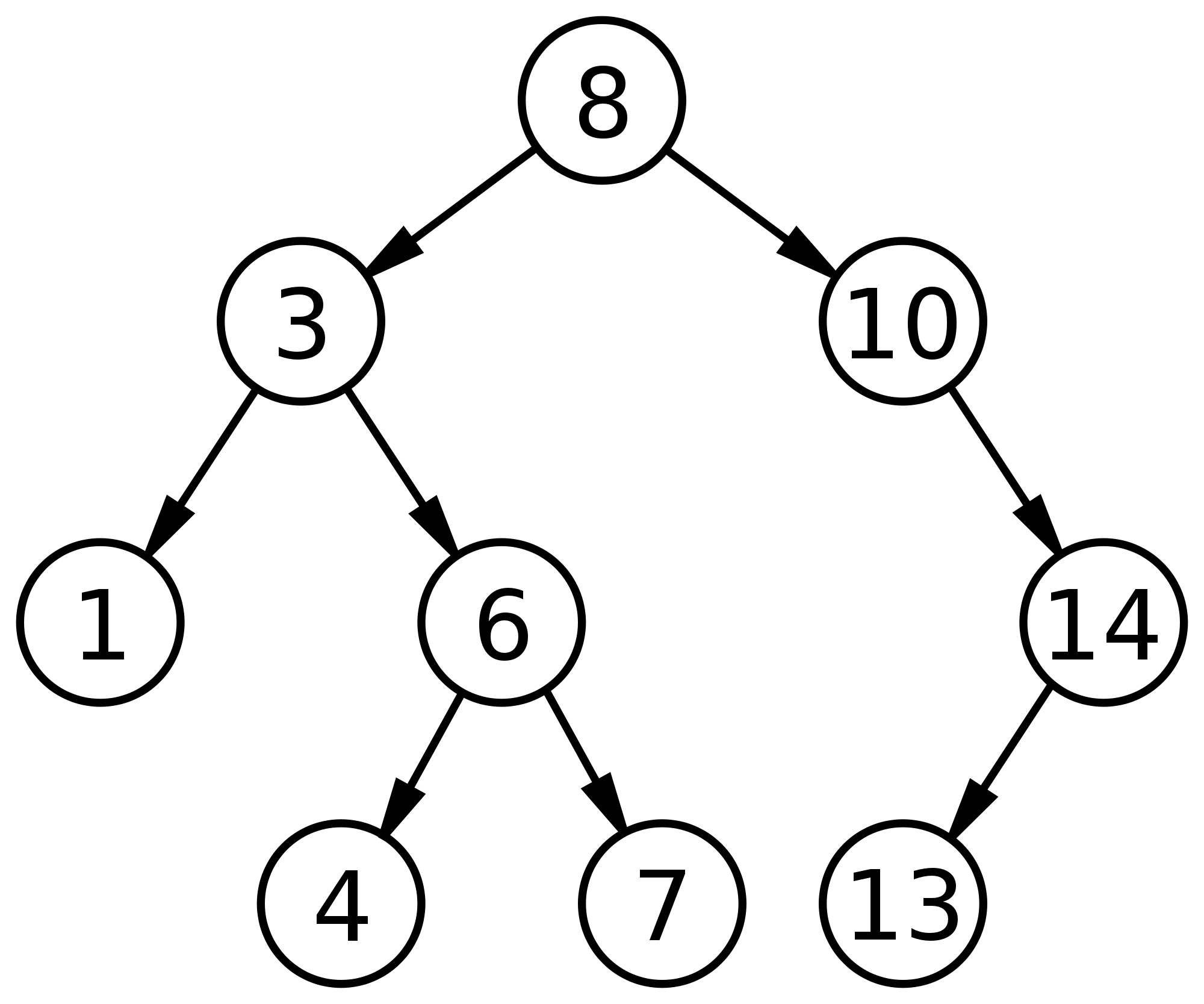

There is a very important property of binary search trees that you should be aware of: “for a node with key k , every key in the left subtree is less than k and every key in the right subtree is greater than k”: Let us consider the following binary search tree:

Let us assume the current number we are processing and just inserted into the tree is 4, meaning that all the numbers to the left of 4 have already been inserted into the tree. How do we tell how many numbers are smaller than 4 (1 and 3)?

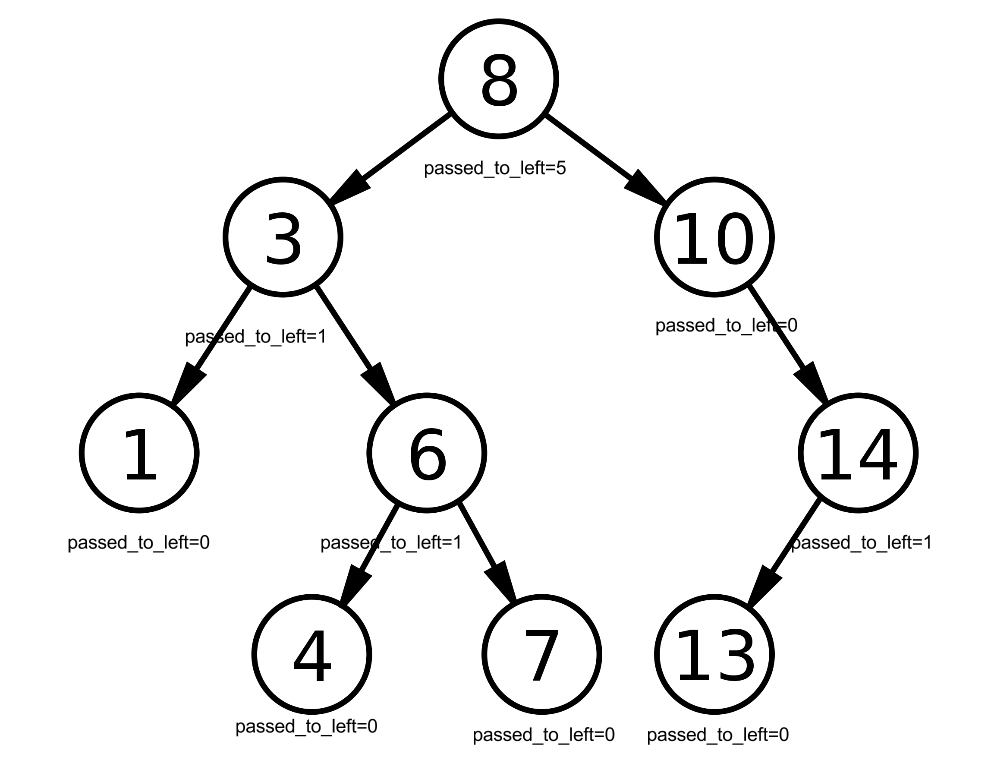

The generalized answer to this question would be to store additional information at every node in the tree. As you insert a node into a tree and it trickles down the tree to its new correct location you can at every node store which path the node has passed. For example for the 8 node if we store how many nodes passed to the left (5 total) then you can very quickly find out how many numbers are smaller than 8 without having to explicitly know what the numbers are ( a major time saver ). For point of example we will refer to the the number of values passed to the left (stored at every node) as passed_to_left.

If we assume 13 is the current number being processed and we want to know how many numbers are less than 13 then we have to start at the root node (8) and proceed down to 13 and count all the left path when we go right as well as counting the nodes we go through themselves.

Therefore to calculate the numbers less than 13 we would have to follow the following logic:

less_than_13 = 0

Is 8 equal to 13? No.

Is 8 less than 13? Yes. All numbers that are less than 8 are also less than 13 so we must include all passed_to_left of 8 to less_than_13 including 8 itself: less_than_13 = less_than_13 + 8.passed_to_left + 1

less_than_13 = 0+5+1 = 6

Now we shift down to 10 in our search for 13 since 13 > 8 and therefore 13 must be in right subtree of 8.

Is 10 equal to 13? No.

Is 10 less than 13? Yes. All numbers that are less than 10 are also less than 13 so we must include all passed_to_left of 10 to less_than_13 including 10 itself: less_than_13 = less_than_13 + 10.passed_to_left + 1

less_than_13 = 6+0+1 = 7

Now we shift down to 14 in our search for 13 since 13 > 10 and therefore 13 must be in right subtree of 10.

Is 14 equal to 13? No.

Is 14 greater than 13? Yes. We can't be sure that all numbers that passed to left of 14 are bigger than 13 so must go down to left subtree of 14 to check.

Now we are down to 13.

Is 13 equal to 13? Yes. Add passed_to_left to less_than_13: less_than_13 = less_than_13 + 13.passed_to_left

less_than_13 = 7+0 = 7Therefore there are 7 numbers in this tree that are less than 13 (as you can visually confirm).

Those familiar with coding and binary search trees will see that this is not too difficult to implement with some recursion.

We recall that we also need to keep track of the numbers that are bigger than the current number and are to the right. One way I managed to do this is to first insert all the numbers into the tree while keeping track of passed_to_left. After this, starting with the last number and going all the way back to the first number you cancel the passed_to_left update for that given number but now do the opposite by storing the right path update ( to be able to tell what how many nodes are bigger than a given node). As you are doing this you can compute the appropriate a * b value and therefore overall triple count after going all the way from right to left. Updating the equivalent passed_to_right is very similar to passed_to_left due to the symmetry of binary search trees.

While updating the right path and left path data I was now able to determine how many numbers are bigger to the right and how many numbers are smaller to the left giving me the correct a * b product in log(N) due to binary search properties (average time where N is array size). Finding smaller and bigger numbers for each number in array gave me overall average algorithm run time of Nlog(N). The run time being fast enough to handle all of the hackerrank test cases correctly.

To illustrate, one of the test cases had an array with 55555 integers as input with correct answer of 3368945032206 distinct triples. If I was to find all smaller/bigger numbers by checking all the numbers (as suggested in beginning of Attempt 4) then I would have to check 55554 numbers every single time. However, with the tree implementation it should average out to log base 2 of 55555 which is about 16. Clearly 16 is the better option.

When dealing with the double occurrences of numbers it is important to simply keep track if the number has occurred already or not with respect to current number being processed (do this with an additional data field in tree structure). For example if you are processing the array from left to right while updating the left path occurrences then you want to make sure you don’t double update passed_to_left. When you are going from right to left you want to make sure you don’t remove the passed_to_left occurrence if there is still an another number of same value that has not been processed. When you hit second occurrence of number going from left to right you want to make sure you don’t double update passed_to_right.

If you keep all these ideas in mind then you should be able to reproduce the solution in code and get your very own:

Here is my rough code for those who still have any questions (The solution is so rough that it does not even clean up memory after itself. You have been warned):

Skip ahead if you are not interested in the code

#include <iostream>

#include <stack>

using namespace std;

struct tree{

tree *left;

tree *right;

int value;

int passed_to_left;//how many nodes when inserted into tree had to go to left subtree

int passed_to_right;//how many nodes when inserted into tree had to go to right subtree

int beforeFrequency;

int afterFrequency;

int lastBiggest;

};

tree * newTree(int value){

tree * newT = new tree();

newT->right = NULL;

newT->left = NULL;

newT->value = value;

newT->passed_to_left = 0;

newT->passed_to_right = 0;

newT->beforeFrequency = 1;

newT->afterFrequency = 0;

newT->lastBiggest = 0;

return newT;

}

//Return node in tree that contains num as the value

//if node does not exist then NULL is returned

tree * isNumThere(int num, tree * t){

if(t == NULL){

return NULL;

}

else{

if(num == t->value){

return t;

}

else if(num < t->value){

return isNumThere(num,t->left);

}

else{

return isNumThere(num,t->right);

}

}

return NULL;

}

tree * passed_to_left_only_insert(int num, tree * t){

if(t == NULL){

return newTree(num);

}

else{

if(num == t->value){

t->beforeFrequency++;

}

else if(num < t->value){

t->passed_to_left++;

t->left = passed_to_left_only_insert(num, t->left);

}

else{

t->right = passed_to_left_only_insert(num,t->right);

}

return t;

}

return NULL;

}

void remove_left_occurences(int num, tree *t){

if(num < t->value){

t->passed_to_left--;

remove_left_occurences(num, t->left);

}

else if(num > t->value){

remove_left_occurences(num,t->right);

}

}

void add_right_occurences(int num, tree *t){

if(num < t->value){

add_right_occurences(num, t->left);

}

else if(num > t->value){

t->passed_to_right++;

add_right_occurences(num,t->right);

}

}

long long findNumbersBiggerThanNumAndAfter(int num,tree * t){

if(num == t->value){

return t->passed_to_right;

}

else if(num < t->value){

return t->passed_to_right + findNumbersBiggerThanNumAndAfter(num,t->left)+(t->afterFrequency > 0 ? 1 : 0);

}

else{

return findNumbersBiggerThanNumAndAfter(num,t->right);

}

return 0;

}

long long findNumbersSmallerThanNumAndBefore(int num,tree * t){

if(num == t->value){

return t->passed_to_left;

}

else if(num < t->value){

return findNumbersSmallerThanNumAndBefore(num,t->left);

}

else{

return t->passed_to_left + findNumbersSmallerThanNumAndBefore(num,t->right)+(t->beforeFrequency > 0 ? 1 : 0);

}

return 0;

}

int main() {

int num;cin>>num;

stack<int> numHistory;

tree * t = NULL;

while(cin>>num){

numHistory.push(num);

tree * exists = isNumThere(num,t);

if(exists==NULL){

t = passed_to_left_only_insert(num,t);

}

else{

exists->beforeFrequency++;

}

}

long long result = 0;

while(!numHistory.empty()){

num = numHistory.top();

numHistory.pop();

tree * exists = isNumThere(num,t);

if(exists->afterFrequency == 0){

add_right_occurences(num,t);

}

exists->afterFrequency++;

if(exists->beforeFrequency==1){

remove_left_occurences(num,t);

}

exists->beforeFrequency--;

long beforeAndSmaller = findNumbersSmallerThanNumAndBefore(num,t);

long afterAndBigger = findNumbersBiggerThanNumAndAfter(num,t) - exists->lastBiggest;

exists->lastBiggest = afterAndBigger;

result= result + (beforeAndSmaller*afterAndBigger);

}

cout<<result<<endl;

}Hopefully, you learned something new in my puzzle solution and if you did not then that is okay too.

Non code stuff

Currently in British Columbia before the school term starts. Really excited to be back in Waterloo. Here are some pictures of BC life:

Just had to recently renew my domain name. Hard to believe that it has already been two years since I first purchased it. Time flies.