IPv4 address hunt

Contents |

IntroductionHello dear reader! In this blog post we will solve the following problem:

The blog will read a bit like a verbose explanation of basic programming data structures and optimization in a discover-as-I-go-along fashion. Touching every addressNo matter how our code ends up computing the number of unique addresses, one thing we can be sure of: every line in the file must be visited, because if we skip a line then we might be skipping acknowledging a unique IPv4 address and therefore skipping incrementing our unique address count by one. Furthermore, as suggested in the problem description, accessing the addresses line by line would be a “naive”, inefficient solution - a big reason for which is that there is room for potential parallelism in our solution. We could split the files in to chunks of the file and within each chunk compute unique addresses and then somehow combine the solution at the end for a total unique count. In this section, we are primarily focused on how to visit each line in the file as efficiently as possible so we will avoid the exact uniqueness computing algorithm involved for now. This will allow us to solve the overall problem in separate parts. Since we are just visiting and not handling any computations then we will call our visit of each IPv4 address a simple touch.

Given that our file is 120Gb in size and that the shortest, ASCII represented, address is a four single digit numbers with three dots and a newline character (e.g. Touching 1: naiveIf we parallelize our uniqueness computation then we would likely have multiple processes accessing the file at the same time. Each process would handle a separate chunk of the file. However, let’s not get ahead of ourselves and just focus on reading the lines with one process. Time to get my hands dirty and start coding. Now although I had a link to download a test 120Gb file… I wasn’t going to open that up on my machine due to hardware and network concerns. I needed something smaller and local to test with ASAP. I needed a script to generate the test data. For this I hit up chatgpt:

Chatgpt produced a beautiful The test file starts at The first Go code I wrote here, as a warm up, was This code in Touching 2: seek aheadNext, I decided to try to parallelize my file reading. We could have multiple file readers, all reading the file at the same time at different locations. Before parallelizing, I must figure out how a to have a single reader start reading a file at an arbitrary location. According to documentation, the where

Now let’s do a quick sanity check. From the problem statement: Next up, I decided to write up some code to experiment with the The problem I encounter now is that I am thinking of splitting the file line by line, but We set Running our code we get: Touching 3: parallelizeNow that we have the ability to use

We can define the length of each chunk of file to be read by reader by dividing up the files’s over length in bytes by how many readers we will use. The previously written function We then unleash the readers on each chunk via go routines (All this code is in We also modify the code to be able to take a commandline argument so we can specify how many readers we want. We test our code with reader count in range where we get the output: We have thus cut our read time from about Although our optimization investigation in this section has been on a test Optimizing the data structureIn the previous sections we developed code to have multiple go routines (readers) split and process a file in chunks. This allowed us to process the data quicker than just visiting each file line sequentially from beginning to end. Each reader then summed up the numbers within each section. Once all the routines were done, a global sum was computed of all the lines in the file based on each routine’s sum. Switching back to the original IPv4 address problem, we remind ourselves that we are interested in computing the amount of unique addresses in the overall file. Unfortunately, having go routines compute unique address counts within each file chunk and then summing the count at the end will not work, because a unique count number for each file chunk cannot confirm if the the same address appeared in both file chunks which would lead us to overcount. Therefore, each go routine that processes a portion of the file must output some sort of set of unique addresses. Once we have the sets from each routine we can combine them like a venn diagram of sorts such that we don’t double count the intersecting entries.

Optimizing 1: defaultThe good candidate data structure for this venn diagram like computation would be a set, but as I understand there is no such native structure in golang, so instead I will just use a map/dictionary to mock a set. For the non programming reader of this article - forgive me as I won’t dive too deep into what a map is as it is considered a pretty standard data structure in programming (read more here). There is potential to use some sort of custom data structure that would perhaps take advantage of the fixed structure of the IPv4 addresses. However, with a custom data structure you need to be very careful and do lots of custom tests to be sure it works - I’m just itching to test the 120Gb file! A sturdy structure like the map might just be good enough. Similar to the previous section, I first create a script that can help me generate some test data. I will reuse the script of writing consecutive numbers to a 1Gb I then write some basic go code ( Running the code I get: In a file of Next, I created another test text file such that the random numbers are in a smaller range (from Wow! Even though we are still processing a 1Gb file, when we reduce our random number range and therefore our memory size of our map, our runtime reduces from 1 minute to 6 seconds! This variance in runtime based on the size of the map gives me pause. Perhaps I might have to create some custom data structure or at least consider the data I am dealing with in more detail.

Optimization 2: customLadies and gentleman, for the next part please fasten your seatbelts as there will a lot of paper napkin math that will be annoying to read through! For IPv4 addresses we have about From preliminary googlin’ I confirmed that a hash key in a map is typically 64 bits long

<A>.<B>.<C>.<D> is such that A,B,C,D are in range of [0,255] = [0,2^8-1] meaning we need 8 bits to express each of A,B,C,D. Since the dots are redundant then an address can be expressed as a 32 bits binary structure which is equivalent to some number like 3232235786. Thanks chatgpt for the diagram!If instead of the default map’s Halving the storage is pretty good. That means in the case where our code encounters the maximum amount We can use a clever trick where instead of Our custom data structure reduces our memory requirement from 17Gb to about 0.5Gb which sounds pretty sweet. There are no default bit array data types in Go so I created my own ( see With this custom bit array structure I reran the unique counter on the text file with numbers in range from It now takes We went from using 4.7Gb with our default map in Since there is a direct connection between random numbers in range `[0,2^32-1] and random IPv4 addresses then for counting unique address we will use our custom bit array structure in combination with a function to convert an address to its number equivalent. We will combine this reduction in runtime and memory with the parallel readers from before in the next section. Optimization 3: parallelizeWe will split our file of random numbers into chunks so that we can have multiple processes working at the same time. Each process will separately track its unique numbers encountered in its own bit array. After each process is done, we will need to combine all of their results using exclusive or (XOR) operation. Referring to the venn diagram from before, XOR is our way of preventing from double counting (code is in In the previous section, we discovered that for the purpose of IPv4 address tracking, our bit array will be around 0.5Gb in size. If we have multiple readers then this will be 0.5Gb per reader. There might be a way to optimize our memory usage even further such that we only use one common bit array for all the readers, but this solution would involve more custom coding and writing some lock structure to deal with concurrent access to the bit array. In practice this may actually lead to slower runtime. We will avoid this for now as even with a few threads we are using much less memory than the default golang map approach of 17Gb. Using a bash script we track the runtime and memory usage of our unique number calculating code: Our script confirms that parallelizing reduces runtime, despite a bump in memory usage. We go from 6 seconds to 1 second runtime - this is a great improvement from our initial 1 minute long naive hash approach. Handling the real dataFrom the previous work in I was still not willing to analyze the 120Gb test file on my machine so I fired up an AWS EC2 instance of the t3.2xlarge type ( 8 vCPUs and 32 GiB ) and processing the 120Gb files, with

Interestingly, computing the line count (via Overall, it was fun to code in go. My biggest struggle was remaining consistent between camelCase and snake_case.

|

Introduction

Hello dear reader!

In this blog post we will solve the following problem:

You have a simple text file with IPv4 addresses. An IPv4 address is defined as a unique label for a device on a network, written as four numbers separated by periods where each number is in range of

[0,255](e.g.192.132.44.2). One line is one address, line by line. You should calculate the number of unique addresses in this file using as little memory and time as possible. There is a “naive” algorithm for solving this problem (read line by line, put lines into HashSet). It’s better if your implementation is more complicated and faster than this naive algorithm. The task must be completed in Golang. The file is unlimited in size and can occupy tens and hundreds of gigabytes. A test file could be around 120Gb.

The blog will read a bit like a verbose explanation of basic programming data structures and optimization in a discover-as-I-go-along fashion.

Touching every address

No matter how our code ends up computing the number of unique addresses, one thing we can be sure of: every line in the file must be visited, because if we skip a line then we might be skipping acknowledging a unique IPv4 address and therefore skipping incrementing our unique address count by one.

Furthermore, as suggested in the problem description, accessing the addresses line by line would be a “naive”, inefficient solution - a big reason for which is that there is room for potential parallelism in our solution. We could split the files in to chunks of the file and within each chunk compute unique addresses and then somehow combine the solution at the end for a total unique count.

In this section, we are primarily focused on how to visit each line in the file as efficiently as possible so we will avoid the exact uniqueness computing algorithm involved for now. This will allow us to solve the overall problem in separate parts. Since we are just visiting and not handling any computations then we will call our visit of each IPv4 address a simple touch.

Given that our file is 120Gb in size and that the shortest, ASCII represented, address is a four single digit numbers with three dots and a newline character (e.g. 1.2.3.4\n), with 1 byte per character we get an upper bound of 15 billion address in our file (120GB/8bytes). Although all addresses will not necessarily be the shortest ASCII length-ed address, our estimation is an effective way of giving an upper bound number to what we are working with.

Touching 1: naive

If we parallelize our uniqueness computation then we would likely have multiple processes accessing the file at the same time. Each process would handle a separate chunk of the file. However, let’s not get ahead of ourselves and just focus on reading the lines with one process. Time to get my hands dirty and start coding.

Now although I had a link to download a test 120Gb file… I wasn’t going to open that up on my machine due to hardware and network concerns. I needed something smaller and local to test with ASAP. I needed a script to generate the test data. For this I hit up chatgpt:

> how many ASCII characters would equal 1gb in memory

<chatgpt responds …>

> okay. Given that that is the case, can you write a python script that writes a file of a series of consecutive numbers, starting at one and incrementing by one with each number on a separate line such that the file is near 1gb in size

Chatgpt produced a beautiful generate_file.py script which I executed to get a 1Gb file:

> python3 generate_file.py test.txt

> du -sh test.txt

1.0G test.txt

> head -n 1 test.txt

1

> tail -n 1 test.txt

118485293

The test file starts at 1 and ends with 118485293 for a total 1Gb file size. With this test file, we transform our unique IP address problem to an analogous problem of summing up all the numbers in the file. The summing problem is similar in that there is a big file to be processed where each line needs to be touched. Fortunately, for the summing problem, checking for correctness is a simple O(1) operation as the formula for getting the sum of numbers from 1 to N is SUM_FROM_1_TO_N(N) = (N*(N+1))/2.

The first Go code I wrote here, as a warm up, was basic_read.go (no chatgpt, but I did have to refresh myself on stackoverflow for how to load and read a file). The code sequentially read the file line by line and then added the numbers up in a rolling sum after which I confirmed for sum correctness against the formula:

> go build basic_read.go

> time ./basic_read

Rolling sum: 7019382387890571

Rolling sum matched formula!

./basic_read 12.56s user 0.44s system 102% cpu 12.707 total

This code in basic_read.go would match the naive solution for the unique IPv4 address problem due to reading file line by line from beginning to start.

Touching 2: seek ahead

Next, I decided to try to parallelize my file reading. We could have multiple file readers, all reading the file at the same time at different locations. Before parallelizing, I must figure out how a to have a single reader start reading a file at an arbitrary location. According to documentation, the Seek method could be of assistance here:

func (f *File) Seek(offset int64, whence int)

(ret int64, err error)

where

Seek sets the offset for the next Read or Write on file to offset, interpreted according to whence: 0 means relative to the origin of the file, 1 means relative to the current offset, and 2 means relative to the end.

Now let’s do a quick sanity check. From the problem statement: The file is unlimited in size and can occupy tens and hundreds of gigabytes. The max val for int64 is 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 and Seek offsets in bytes. Thus, if we had a file large enough where int64 max val bytes in would be a file’s halfway mark then as long as our file is less than 9 billion Gb then the Seek offset can easily hit past the halfway point. Therefore, Seek is a good candidate for dealing in our context of files measured in hundreds of Gb.

Next up, I decided to write up some code to experiment with the Seek method. If I Seek somewhere in the middle of a file between number 1 and last number in file 118 485 293 (say 50 000 000) then I can do the rolling sum from that middle number to 118 485 293 and can still verify for sum correctness by subtracting the sums (e.g. SUM_FROM_1_TO_N(118 485 293) - SUM_FROM_1_TO_N(50 000 000-1)).

The problem I encounter now is that I am thinking of splitting the file line by line, but Seek deals in byte offsets meaning that it is possible for me to offset to the middle of a number since each number past 9 is at least two bytes in length when stored in ASCII format. I will have to search for the newline character '\n' as that is what separates each line and new number. I solve this concern in intermediate_sum.go with function:

const MAX_BYTE_COUNT = 11;

/*

We scan MAX_BYTE_COUNT ahead using ReadAt to find the nearest "\n",

after which we return the index of the "\n" + 1 to indicate the next

fresh line of data.

*/

func getNextNewLineByteLocation(f *os.File, startingLocation int64)

( byteOfNearestStartingNewLine int64, err error ) {

...

}

We set MAX_BYTE_COUNT to 11 because in our current case of 1Gb file we have max number 118 485 293 (9 digits) wrapped by a new line '\n' on both sides. In the case of IPv4 addresses, the max length-ed address is 15 (e.g. 255.255.255.255) so we would set MAX_BYTE_COUNT to 17.

Running our code we get:

>./intermediate_read

File size: 1073741828 bytes

Initial offset: 50000000 bytes

File pointer reset offset to fresh line: 50000008 bytes in

The first number, with offset read: 6388890

Rolling sum: 6998973433368966

Rolling sum matched formula!

Touching 3: parallelize

Now that we have the ability to use Seek to read at an arbitrary point in the file, we can now see if we can have multiple readers of the file, each reading their own offset portion in parallel. Each reader would read the numbers and sum them up right up until the next area in the file that another reader was working on. Each reader would store their sum and once all readers are done, the resulting sum would be added up for the grand cumulative sum.

We can define the length of each chunk of file to be read by reader by dividing up the files’s over length in bytes by how many readers we will use. The previously written function getNextNewLineByteLocation will assist us in determining where each reader should start and end to make sure we don’t miss a single line:

We then unleash the readers on each chunk via go routines (All this code is in advanced_read.go):

We also modify the code to be able to take a commandline argument so we can specify how many readers we want. We test our code with reader count in range 1 to 10 (thanks chatgpt for this quick bash script):

for READER_COUNT in {1..10}; do

# Capture the real time from the `time` output

TIME_OUTPUT=$( { time ./advanced_read "$READER_COUNT"; } 2>&1 >/dev/null )

# Extract the "real" elapsed time

TIME=$(echo "$TIME_OUTPUT" | grep real | awk '{print $2}')

echo "READER_COUNT: $READER_COUNT, TIME_TO_RUN: $TIME"

done

where we get the output:

READER_COUNT: 1, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m13.245s

READER_COUNT: 2, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m7.289s

READER_COUNT: 3, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m5.262s

READER_COUNT: 4, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m4.229s

READER_COUNT: 5, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m3.671s

READER_COUNT: 6, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m3.558s

READER_COUNT: 7, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m3.611s

READER_COUNT: 8, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m3.590s

READER_COUNT: 9, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m3.602s

READER_COUNT: 10, TIME_TO_RUN: 0m3.641s

We have thus cut our read time from about 13.2 seconds to 3.5 when we parallelize our reading operation (roughly 70% improvement)! The formula SUM_FROM_1_TO_N is used here to make sure that despite our reduction in runtime, no line is missed, via some sort of off-by-one error, in computing the overall sum.

Although our optimization investigation in this section has been on a test 1Gb file for a number counting problem, we now have some hope that the IPv4 address processing code we will write will parse the text file faster than the naive line by line approach if it has multiple readers.

Optimizing the data structure

In the previous sections we developed code to have multiple go routines (readers) split and process a file in chunks. This allowed us to process the data quicker than just visiting each file line sequentially from beginning to end. Each reader then summed up the numbers within each section. Once all the routines were done, a global sum was computed of all the lines in the file based on each routine’s sum.

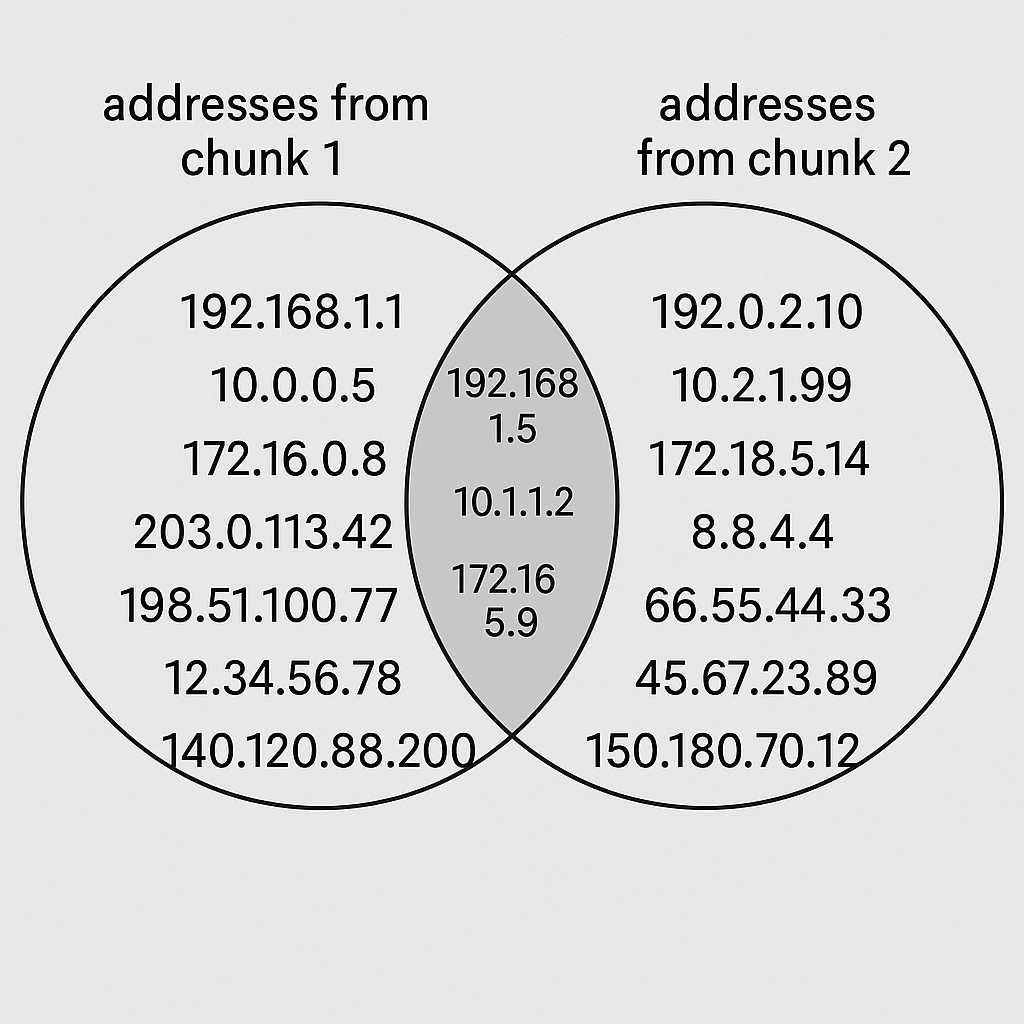

Switching back to the original IPv4 address problem, we remind ourselves that we are interested in computing the amount of unique addresses in the overall file. Unfortunately, having go routines compute unique address counts within each file chunk and then summing the count at the end will not work, because a unique count number for each file chunk cannot confirm if the the same address appeared in both file chunks which would lead us to overcount.

Therefore, each go routine that processes a portion of the file must output some sort of set of unique addresses. Once we have the sets from each routine we can combine them like a venn diagram of sorts such that we don’t double count the intersecting entries.

Optimizing 1: default

The good candidate data structure for this venn diagram like computation would be a set, but as I understand there is no such native structure in golang, so instead I will just use a map/dictionary to mock a set. For the non programming reader of this article - forgive me as I won’t dive too deep into what a map is as it is considered a pretty standard data structure in programming (read more here).

There is potential to use some sort of custom data structure that would perhaps take advantage of the fixed structure of the IPv4 addresses. However, with a custom data structure you need to be very careful and do lots of custom tests to be sure it works - I’m just itching to test the 120Gb file! A sturdy structure like the map might just be good enough.

Similar to the previous section, I first create a script that can help me generate some test data. I will reuse the script of writing consecutive numbers to a 1Gb test.txt file from before, but instead of consecutive numbers, I will set it to be a random number on each line. Our objective will be not getting a sum of all numbers, but computing how many unique numbers there are - similar to computing how many unique IPv4 addresses there are.

I then write some basic go code (basic_unique.go) that reads the file of random numbers line by line with a single reader and counts up unique counts using a the default map structure. The code is so short that I’ll just paste it here:

Running the code I get:

> go build basic_unique.go

> time ./basic_unique

Unique numbers: 102894356

./basic_unique 43.04s user 35.84s system 114% cpu 1:08.86 total

> wc -l test.txt

108580761 test.txt

In a file of 108 580 761 lines we get 102 894 356 unique entries ( or in other words we have that about 5% of the lines are duplicates). The code execution is over a minute in length which compared to basic_read from before, where we summed up numbers instead of storing unique numbers, is 5 times slower (compared to 12 seconds)!

Next, I created another test text file such that the random numbers are in a smaller range (from 1 to 1 000) in order for the size of unique_map in our code be smaller.

> time ./basic_unique

Unique numbers: 1000

./basic_unique 6.44s user 0.21s system 100% cpu 6.618 total

> wc -l test2.txt

275813149 test2.txt

Wow! Even though we are still processing a 1Gb file, when we reduce our random number range and therefore our memory size of our map, our runtime reduces from 1 minute to 6 seconds!

This variance in runtime based on the size of the map gives me pause. Perhaps I might have to create some custom data structure or at least consider the data I am dealing with in more detail.

Optimization 2: custom

Ladies and gentleman, for the next part please fasten your seatbelts as there will a lot of paper napkin math that will be annoying to read through!

For IPv4 addresses we have about 4 billion possible address ( <A>.<B>.<C>.<D> where A,B,C,D are in range of [0,255] which leads to 256^4 = (2^8)^4 = 2^32 = 4 294 967 296 possible addresses ). Furthermore, we previously discussed how a 120Gb file might contain 15 billion IPv4 addresses which means that for a 120Gb or bigger file we expect to have many duplicates as line count significantly exceeds unique address count.

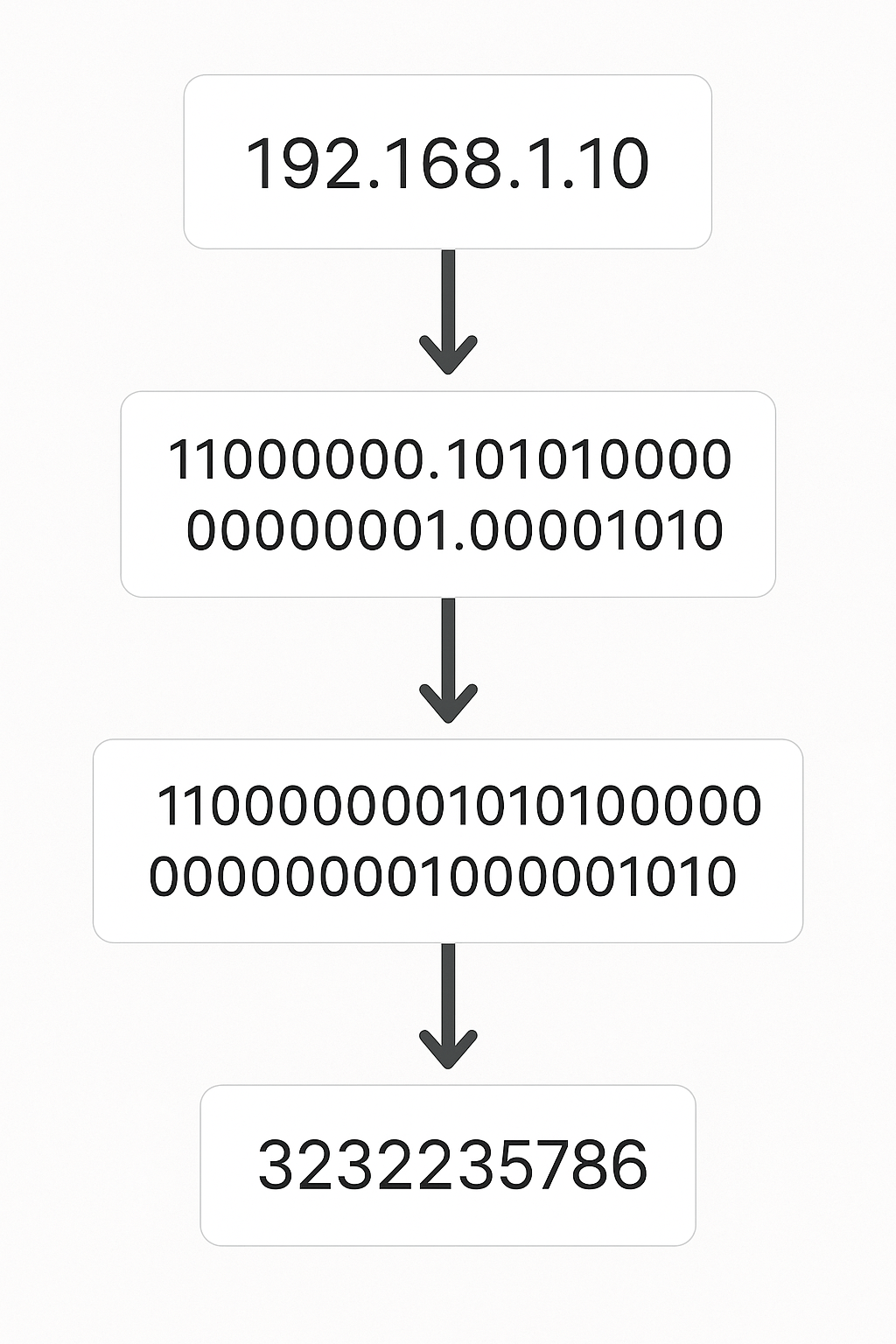

From preliminary googlin’ I confirmed that a hash key in a map is typically 64 bits long (8 bytes). This means a number 123 key in a map stored as unique_map[123] = struct{}{} (in range 1 to N) will be stored as a 64 bit value. Given that there are 64 bits and each bit can be 0 or 1 then the map can store 2^64 (18 446 744 073 709 551 616) possible keys. This number is much bigger than the possible IPv4 addresses. As implied in the previous paragraph, we only need 32 bits (from the 256^4 = 2^32 calculation) to represent all the IPv4 addresses - each IPv4 address can be represented by a 32 bit number (see diagram below).

<A>.<B>.<C>.<D> is such that A,B,C,D are in range of [0,255] = [0,2^8-1] meaning we need 8 bits to express each of A,B,C,D. Since the dots are redundant then an address can be expressed as a 32 bits binary structure which is equivalent to some number like 3232235786. Thanks chatgpt for the diagram!If instead of the default map’s 64 bit hash keys, we use 32 bit keys to match the maximum bits needs to store a IPv4 address, we can cut half our memory taken up by our map.

Halving the storage is pretty good. That means in the case where our code encounters the maximum amount 2^32 of unique IPv4 addresses then our map will have 2^32 keys where each key is 32 = 2^5 bits long. This means that our memory usage will be about 2^32*2^5 = 2^37 bits which is about 17Gb. This still sounds too much … that’s like the memory taken up by at least a few full length movie files.

We can use a clever trick where instead of 2^37 map structure we just need a bit array of length 2^32 where if the ith entry in the bit array is binary 1 then that represents that the number i was encountered (or its IPv4 equivalent). With this bit array we don’t explicitly store the number i which was the case in the previous paragraph with storing each 32 bit long key. The default map structure might perform better in the cases there are few unique IPv4 addresses as most of our bit array will be idling binary zeros, but that is fine given that we are dealing with such large test files that we are likely dealing with a higher unique count.

Our custom data structure reduces our memory requirement from 17Gb to about 0.5Gb which sounds pretty sweet.

There are no default bit array data types in Go so I created my own ( see intermediate_unique.go along with the tests needed for some basic confidence in correctness). To compute the amount of unique entries stored in our bit array, we just count all the entries set to binary 1.

With this custom bit array structure I reran the unique counter on the text file with numbers in range from 1 to 1 000 000 000

> time ./intermediate_unique

Unique numbers: 102894356

./intermediate_unique 6.32s user 0.20s system 100% cpu 6.519 total

It now takes 10% of the previous 1 minute runtime. Our custom data structure was able to significantly reduce our runtime. I also wanted to confirm that I am actually using less memory now:

> gtime -f "Max Memory: %M KB" ./basic_unique

Unique numbers: 102894356

Max Memory: 4731040 KB

> gtime -f "Max Memory: %M KB" ./intermediate_unique

Unique numbers: 102894356

Max Memory: 136816 KB

We went from using 4.7Gb with our default map in basic_unique.go to 0.13Gb in intermediate_unique.go (the latter is less than the aforementioned 0.5Gb estimate because the bit array code was customized to use minimum amount of memory required to handle the known largest possible number to be encountered (in our test case 1 000 000 000 - needs 30 bits instead of full 32)) .

Since there is a direct connection between random numbers in range `[0,2^32-1] and random IPv4 addresses then for counting unique address we will use our custom bit array structure in combination with a function to convert an address to its number equivalent.

We will combine this reduction in runtime and memory with the parallel readers from before in the next section.

Optimization 3: parallelize

We will split our file of random numbers into chunks so that we can have multiple processes working at the same time. Each process will separately track its unique numbers encountered in its own bit array. After each process is done, we will need to combine all of their results using exclusive or (XOR) operation. Referring to the venn diagram from before, XOR is our way of preventing from double counting (code is in advanced_unique.go)

In the previous section, we discovered that for the purpose of IPv4 address tracking, our bit array will be around 0.5Gb in size. If we have multiple readers then this will be 0.5Gb per reader.

There might be a way to optimize our memory usage even further such that we only use one common bit array for all the readers, but this solution would involve more custom coding and writing some lock structure to deal with concurrent access to the bit array. In practice this may actually lead to slower runtime. We will avoid this for now as even with a few threads we are using much less memory than the default golang map approach of 17Gb.

Using a bash script we track the runtime and memory usage of our unique number calculating code:

> ./bash_script.sh

READER_COUNT: 1, RUNTIME: 6.53s, MAX_MEM: 0.255 GB

READER_COUNT: 2, RUNTIME: 3.37s, MAX_MEM: 0.380 GB

READER_COUNT: 3, RUNTIME: 2.41s, MAX_MEM: 0.505 GB

READER_COUNT: 4, RUNTIME: 1.89s, MAX_MEM: 0.631 GB

READER_COUNT: 5, RUNTIME: 1.56s, MAX_MEM: 0.756 GB

READER_COUNT: 6, RUNTIME: 1.46s, MAX_MEM: 0.881 GB

READER_COUNT: 7, RUNTIME: 1.37s, MAX_MEM: 1.006 GB

READER_COUNT: 8, RUNTIME: 1.32s, MAX_MEM: 1.131 GB

READER_COUNT: 9, RUNTIME: 1.28s, MAX_MEM: 1.257 GB

READER_COUNT: 10, RUNTIME: 1.23s, MAX_MEM: 1.382 GB

READER_COUNT: 11, RUNTIME: 1.19s, MAX_MEM: 1.507 GB

READER_COUNT: 12, RUNTIME: 1.20s, MAX_MEM: 1.632 GB

READER_COUNT: 13, RUNTIME: 1.18s, MAX_MEM: 1.757 GB

READER_COUNT: 14, RUNTIME: 1.21s, MAX_MEM: 1.883 GB

READER_COUNT: 15, RUNTIME: 1.21s, MAX_MEM: 2.008 GB

Our script confirms that parallelizing reduces runtime, despite a bump in memory usage. We go from 6 seconds to 1 second runtime - this is a great improvement from our initial 1 minute long naive hash approach.

Handling the real data

From the previous work in Touching every address and Optimizing the data structure, we now have code (in unique_address_count.go) that can process a file of IPv4 addresses efficiently - at least more so than the default approach of reading the stuff line by line and using a hash set. Now how does it handle a more challenging data set?

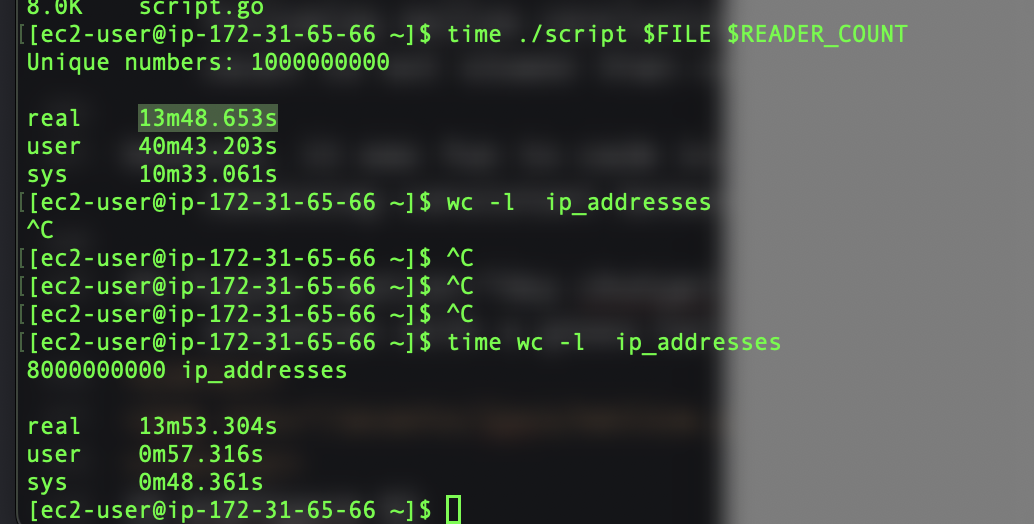

I was still not willing to analyze the 120Gb test file on my machine so I fired up an AWS EC2 instance of the t3.2xlarge type ( 8 vCPUs and 32 GiB ) and processing the 120Gb files, with 20 go routines, took 14 minutes which counted 1 000 000 000 unique addresses in a file with 8 000 000 000 lines.

Interestingly, computing the line count (via wc -l) also took 14 minutes, but this is not to suggest that my unique_address_count.go is (overly) deficient in my implementation since wc code does not have to carry bit arrays in memory. I think the equal wc timing leads me to the following mellow conclusion: at least computing unique line count is not slower than computing total line count.

Overall, it was fun to code in go. My biggest struggle was remaining consistent between camelCase and snake_case.